Lilith

This article is about the Jewish mythological figure Lilith. For other uses, see Lilith (disambiguation).

Lilith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | |

Lilith (/ˈlɪlɪθ/; Hebrew: לִילִית Lîlîṯ) is a figure in Jewish mythology, developed earliest in the Babylonian Talmud (3rd to 5th century AD). From c. AD 700–1000 onwards Lilith appears as Adam's first wife, created at the same time (Rosh Hashanah) and from the same clay as Adam—compare Genesis 1:27.[1] The figure of Lilith may relate in part to a historically earlier class of female demons (Akkadian: 𒆤𒆤𒄄𒀀, romanized: lilîtu) in ancient Mesopotamian religion, found in cuneiform texts of Sumer, the Akkadian Empire, Assyria, and Babylonia.

Lilith continues to serve as source material in modern Western culture, literature, occultism, fantasy, and horror.

History[edit]

In some Jewish folklore, such as the satiric Alphabet of Sirach (c. AD 700–1000), Lilith appears as Adam's first wife, who was created at the same time (Rosh Hashanah) and from the same clay as Adam — compare Genesis 1:27 (this contrasts with Eve, who was created from one of Adam's ribs: Genesis 2:22). The legend of Lilith developed extensively during the Middle Ages, in the tradition of Aggadah, the Zohar, and Jewish mysticism.[2] For example, in the 13th-century writings of Isaac ben Jacob ha-Cohen, Lilith left Adam after she refused to become subservient to him and then would not return to the Garden of Eden after she had coupled with the archangel Samael.[3]

Interpretations of Lilith found in later Jewish materials are plentiful, but little information has survived relating to the Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian and Babylonian view of this class of demons. While researchers almost universally agree that a connection exists, recent scholarship has disputed the relevance of two sources previously used to connect the Jewish lilith to an Akkadian lilītu — the Gilgamesh appendix and the Arslan Tash amulets.[4] (see below for discussion of these two problematic sources) "Other scholars, such as Lowell K. Handy, agree that Lilith derives from Mesopotamian demons but argue against finding evidence of the Hebrew Lilith in many of the epigraphical and artifactual sources frequently cited as such (e.g., the Sumerian Gilgamesh fragment, the Sumerian incantation from Arshlan-Tash)."[3]:174

In Hebrew-language texts, the term lilith or lilit (translated as "night-creatures", "night-monster", "night-hag", or "screech-owl") first occurs in a list of animals in Isaiah 34:14, either in singular or plural form according to variations in the earliest manuscripts. The Isaiah 34:14 Lilith reference does not appear in most common Bible translations such as KJV and NIV. Commentators and interpreters often envision the figure of Lilith as a dangerous demon of the night, who is sexually wanton, and who steals babies in the darkness. In the Dead Sea Scrolls 4Q510-511, the term first occurs in a list of monsters. Jewish magical inscriptions on bowls and amulets from the 6th century AD onwards identify Lilith as a female demon and provide the first visual depictions of her.

Etymology[edit]

In the Akkadian language of Assyria and Babylonia, the terms lili and līlītu mean spirits. Some uses of līlītu are listed in The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (CAD, 1956, L.190), in Wolfram von Soden's Akkadisches Handwörterbuch (AHw, p. 553), and Reallexikon der Assyriologie (RLA, p. 47).[5]

The Sumerian female demons lili have no etymological relation to Akkadian lilu, "evening".[6]

Archibald Sayce (1882)[7] considered that Hebrew lilit (or lilith) לילית and the earlier Akkadian līlītu are from proto-Semitic. Charles Fossey (1902) has this literally translating to "female night being/demon", although cuneiform inscriptions from Mesopotamia exist where Līlīt and Līlītu refers to disease-bearing wind spirits.[8]

Mesopotamian mythology[edit]

The spirit in the tree in the Gilgamesh cycle[edit]

Samuel Noah Kramer (1932, published 1938)[9] translated ki-sikil-lil-la-ke as Lilith in "Tablet XII" of the Epic of Gilgamesh dated c. 600 BC. "Tablet XII" is not part of the Epic of Gilgamesh, but is a later Assyrian Akkadian translation of the latter part of the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh.[10] The ki-sikil-lil-la-ke is associated with a serpent and a zu bird.[11] In Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld, a huluppu tree grows in Inanna's garden in Uruk, whose wood she plans to use to build a new throne. After ten years of growth, she comes to harvest it and finds a serpent living at its base, a Zu bird raising young in its crown, and that a ki-sikil-lil-la-ke made a house in its trunk. Gilgamesh is said to have killed the snake, and then the zu bird flew away to the mountains with its young, while the ki-sikil-lil-la-ke fearfully destroys its house and runs for the forest.[12][13] Identification of ki-sikil-lil-la-ke as Lilith is stated in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (1999).[14] According to a new source from late antiquity, Lilith appears in a Mandaic magic story where she is considered to represent the branches of a tree with other demonic figures that form other parts of the tree, though this may also include multiple "Liliths".[15]

Suggested translations for the Tablet XII spirit in the tree include ki-sikil as "sacred place", lil as "spirit", and lil-la-ke as "water spirit",[16] but also simply "owl", given that the lil is building a home in the trunk of the tree.[17]

A connection between the Gilgamesh ki-sikil-lil-la-ke and the Jewish Lilith was rejected by Dietrich Opitz (1932)[18][failed verification] and rejected on textual grounds by Sergio Ribichini (1978).[19]

The bird-footed woman in the Burney Relief[edit]

Kramer's translation of the Gilgamesh fragment was used by Henri Frankfort (1937)[20] and Emil Kraeling (1937)[21] to support identification of a woman with wings and bird-feet in the Burney Relief as related to Lilith. Frankfort and Kraeling incorrectly identified the figure in the relief with Lilith, based on a misreading of an outdated translation of the Epic of Gilgamesh.[22] Modern research has identified the figure as one of the main goddesses of the Mesopotamian pantheons, most probably Inanna or Ereshkigal.[23]

The Arslan Tash amulets[edit]

The Arslan Tash amulets are limestone plaques discovered in 1933 at Arslan Tash, the authenticity of which is disputed. William F. Albright, Theodor H. Gaster,[24] and others, accepted the amulets as a pre-Jewish source which shows that the name Lilith already existed in the 7th century BC but Torczyner (1947) identified the amulets as a later Jewish source.[25]

In the Hebrew Bible[edit]

The word lilit (or lilith) only appears once in the Hebrew Bible, in a prophecy regarding the fate of Edom,[26] while the other seven terms in the list appear more than once and thus are better documented. The reading of scholars and translators is often guided by a decision about the complete list of eight creatures as a whole.[27][28][29] Quoting from Isaiah 34 (NAB):

Hebrew text[edit]

In the Masoretic Text:

In the Dead Sea Scrolls, among the 19 fragments of Isaiah found at Qumran, the Great Isaiah Scroll (1Q1Isa) in 34:14 renders the creature as plural liliyyot (or liliyyoth).[32][33]

Eberhard Schrader (1875)[34] and Moritz Abraham Levy (1855)[35] suggest that Lilith was a demon of the night, known also by the Jewish exiles in Babylon. Schrader's and Levy's view is therefore partly dependent on a later dating of Deutero-Isaiah to the 6th century BC, and the presence of Jews in Babylon which would coincide with the possible references to the Līlītu in Babylonian demonology. However, this view is challenged by some modern research such as by Judit M. Blair (2009) who considers that the context indicates unclean animals.[36]

Greek version[edit]

The Septuagint translates both the reference to lilith and the word for jackals or "wild beasts of the island" within the same verse into Greek as onokentauros, apparently assuming them as referring to the same creatures and gratuitously omitting "wildcats/wild beasts of the desert" (so, instead of the wildcats or desert beasts meeting with the jackals or island beasts, the goat or "satyr" crying "to his fellow" and lilith or "screech-owl" resting "there", it is the goat or "satyr", translated as daimonia "demons", and the jackals or island beasts "onocentaurs" meeting with each other and crying "one to the other" and the latter resting there in the translation).[37]

Latin Bible[edit]

The early 5th-century Vulgate translated the same word as lamia.[38][39]

The translation is, "And demons shall meet with monsters, and one hairy one shall cry out to another; there the lamia has lain down and found rest for herself".

English versions[edit]

Wycliffe's Bible (1395) preserves the Latin rendering lamia:

The Bishops' Bible of Matthew Parker (1568) from the Latin:

Douay–Rheims Bible (1582/1610) also preserves the Latin rendering lamia:

The Geneva Bible of William Whittingham (1587) from the Hebrew:

Then the King James Version (1611):

The "screech owl" translation of the King James Version is, together with the "owl" (yanšup, probably a water bird) in 34:11 and the "great owl" (qippoz, properly a snake) of 34:15, an attempt to render the passage by choosing suitable animals for difficult-to-translate Hebrew words.

Later translations include:

- night-owl (Young, 1898)

- night-spectre (Rotherham, Emphasized Bible, 1902)

- night monster (ASV, 1901; JPS 1917, Good News Translation, 1992; NASB, 1995)

- vampires (Moffatt Translation, 1922; Knox Bible, 1950)

- night hag (Revised Standard Version, 1947)

- Lilith (Jerusalem Bible, 1966)

- lilith (New American Bible, 1970)

- Lilith (New Revised Standard Version, 1989)

- Lilith (The Message (Bible), Peterson, 1993)

- night creature (New International Version, 1978; New King James Version, 1982; New Living Translation, 1996, Today's New International Version)

- nightjar (New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures, 1984)

- night bird (English Standard Version, 2001)

Jewish tradition[edit]

Major sources in Jewish tradition regarding Lilith in chronological order include:

- c. 40–10 BC Dead Sea Scrolls – Songs for a Sage (4Q510-511)

- c. 200 Mishnah – not mentioned

- c. 500 Gemara of the Talmud

- c. 800 The Alphabet of Ben-Sira

- c. 900 Midrash Abkir

- c. 1260 Treatise on the Left Emanation, Spain

- c. 1280 Zohar, Spain.

Dead Sea Scrolls[edit]

The Dead Sea Scrolls contain one indisputable reference to Lilith in Songs of the Sage (4Q510–511)[40] fragment 1:

As with the Massoretic text of Isaiah 34:14, and therefore unlike the plural liliyyot (or liliyyoth) in the Isaiah scroll 34:14, lilit in 4Q510 is singular, this liturgical text both cautions against the presence of supernatural malevolence and assumes familiarity with Lilith; distinct from the biblical text, however, this passage does not function under any socio-political agenda, but instead serves in the same capacity as An Exorcism (4Q560) and Songs to Disperse Demons (11Q11).[42] The text is thus, to a community "deeply involved in the realm of demonology",[43] an exorcism hymn.

Joseph M. Baumgarten (1991) identified the unnamed woman of The Seductress (4Q184) as related to female demon.[44] However, John J. Collins[45] regards this identification as "intriguing" but that it is "safe to say" that (4Q184) is based on the strange woman of Proverbs 2, 5, 7, 9:

Early Rabbinic literature[edit]

Lilith does not occur in the Mishnah. There are five references to Lilith in the Babylonian Talmud in Gemara on three separate Tractates of the Mishnah:

- "Rab Judah citing Samuel ruled: If an abortion had the likeness of Lilith its mother is unclean by reason of the birth, for it is a child but it has wings." (Babylonian Talmud on Tractate Nidda 24b)[46]

- "[Expounding upon the curses of womanhood] In a Baraitha it was taught: She grows long hair like Lilith, sits when making water like a beast, and serves as a bolster for her husband." (Babylonian Talmud on Tractate Eruvin 100b)

- "For gira he should take an arrow of Lilith and place it point upwards and pour water on it and drink it. Alternatively he can take water of which a dog has drunk at night, but he must take care that it has not been exposed." (Babylonian Talmud, tractate Gittin 69b). In this particular case, the "arrow of Lilith" is most probably a scrap of meteorite or a fulgurite, colloquially known as "petrified lightning" and treated as antipyretic medicine.[47]

- "Rabbah said: I saw how Hormin the son of Lilith was running on the parapet of the wall of Mahuza, and a rider, galloping below on horseback could not overtake him. Once they saddled for him two mules which stood on two bridges of the Rognag; and he jumped from one to the other, backward and forward, holding in his hands two cups of wine, pouring alternately from one to the other, and not a drop fell to the ground." (Babylonian Talmud, tractate Bava Bathra 73a-b). Hormin who is mentioned here as the son of Lilith is most probably a result of a scribal error of the word "Hormiz" attested in some of the Talmudic manuscripts. The word itself in turn seems to be a distortion of Ormuzd, the Zendavestan deity of light and goodness. If so, it is somewhat ironic that Ormuzd becomes here the son of a nocturnal demon.[47]

- "R. Hanina said: One may not sleep in a house alone [in a lonely house], and whoever sleeps in a house alone is seized by Lilith." (Babylonian Talmud on Tractate Shabbath 151b)

The above statement by Hanina may be related to the belief that nocturnal emissions engendered the birth of demons:

- "R. Jeremiah b. Eleazar further stated: In all those years [130 years after his expulsion from the Garden of Eden] during which Adam was under the ban he begot ghosts and male demons and female demons [or night demons], for it is said in Scripture: And Adam lived a hundred and thirty years and begot a son in own likeness, after his own image, from which it follows that until that time he did not beget after his own image ... When he saw that through him death was ordained as punishment he spent a hundred and thirty years in fasting, severed connection with his wife for a hundred and thirty years, and wore clothes of fig on his body for a hundred and thirty years. – That statement [of R. Jeremiah] was made in reference to the semen which he emitted accidentally." (Babylonian Talmud on Tractate Eruvin 18b)

The Midrash Rabbah collection contains two references to Lilith. The first one is present in Genesis Rabbah 22:7 and 18:4: according to Rabbi Hiyya God proceeded to create a second Eve for Adam, after Lilith had to return to dust.[48] However, to be exact the said passages do not employ the Hebrew word lilith itself and instead speak of "the first Eve" (Heb. Chavvah ha-Rishonah, analogically to the phrase Adam ha-Rishon, i.e. the first Adam). Although in the medieval Hebrew literature and folklore, especially that reflected on the protective amulets of various kinds, Chavvah ha-Rishonah was identified with Lilith, one should remain careful in transposing this equation to the Late Antiquity.[47]

The second mention of Lilith, this time explicit, is present in Numbers Rabbah 16:25. The midrash develops the story of Moses's plea after God expresses anger at the bad report of the spies. Moses responds to a threat by God that He will destroy the Israelite people. Moses pleads before God, that God should not be like Lilith who kills her own children.[47] Moses said:

Incantation bowls[edit]

An individual Lilith, along with Bagdana "king of the lilits", is one of the demons to feature prominently in protective spells in the eighty surviving Jewish occult incantation bowls from Sassanid Empire Babylon (4th–6th century AD) with influence from Iranian culture.[47][50] These bowls were buried upside down below the structure of the house or on the land of the house, in order to trap the demon or demoness.[51] Almost every house was found to have such protective bowls against demons and demonesses.[51][52]

The centre of the inside of the bowl depicts Lilith, or the male form, Lilit. Surrounding the image is writing in spiral form; the writing often begins at the centre and works its way to the edge.[53] The writing is most commonly scripture or references to the Talmud. The incantation bowls which have been analysed, are inscribed in the following languages, Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, Syriac, Mandaic, Middle Persian, and Arabic. Some bowls are written in a false script which has no meaning.[50]

The correctly worded incantation bowl was capable of warding off Lilith or Lilit from the household. Lilith had the power to transform into a woman's physical features, seduce her husband, and conceive a child. However, Lilith would become hateful towards the children born of the husband and wife and would seek to kill them. Similarly, Lilit would transform into the physical features of the husband, seduce the wife, she would give birth to a child. It would become evident that the child was not fathered by the husband, and the child would be looked down on. Lilit would seek revenge on the family by killing the children born to the husband and wife.[54]

Key features of the depiction of Lilith or Lilit include the following. The figure is often depicted with arms and legs chained, indicating the control of the family over the demon(ess). The demon(ess) is depicted in a frontal position with the whole face showing. The eyes are very large, as well as the hands (if depicted). The demon(ess) is entirely static.[50]

One bowl contains the following inscription commissioned from a Jewish occultist to protect a woman called Rashnoi and her husband from Lilith:

Alphabet of Ben Sira[edit]

The pseudepigraphical[56] 8th–10th centuries Alphabet of Ben Sira is considered to be the oldest form of the story of Lilith as Adam's first wife. Whether this particular tradition is older is not known. Scholars tend to date the Alphabet between the 8th and 10th centuries AD. The work has been characterised as satirical.

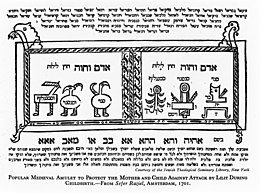

In the text an amulet is inscribed with the names of three angels (Senoy, Sansenoy, and Semangelof) and placed around the neck of newborn boys in order to protect them from the lilin until their circumcision.[57] The amulets used against Lilith that were thought to derive from this tradition are, in fact, dated as being much older.[58] The concept of Eve having a predecessor is not exclusive to the Alphabet, and is not a new concept, as it can be found in Genesis Rabbah. However, the idea that Lilith was the predecessor may be exclusive to the Alphabet.

The idea in the text that Adam had a wife prior to Eve may have developed from an interpretation of the Book of Genesis and its dual creation accounts; while Genesis 2:22 describes God's creation of Eve from Adam's rib, an earlier passage, 1:27, already indicates that a woman had been made: "So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them." The Alphabet text places Lilith's creation after God's words in Genesis 2:18 that "it is not good for man to be alone"; in this text God forms Lilith out of the clay from which he made Adam but she and Adam bicker. Lilith claims that since she and Adam were created in the same way they were equal and she refuses to submit to him:

The background and purpose of The Alphabet of Ben-Sira is unclear. It is a collection of stories about heroes of the Bible and Talmud, it may have been a collection of folk-tales, a refutation of Christian, Karaite, or other separatist movements; its content seems so offensive to contemporary Jews that it was even suggested that it could be an anti-Jewish satire,[59] although, in any case, the text was accepted by the Jewish mystics of medieval Germany. In turn, other scholars argue that the target of the Alphabet's satire is very difficult to establish exactly because of the variety of the figures and values ridiculed therein: criticism is actually directed against Adam, who turns out to be weak and ineffective in his relations with his wife. Apparently, the first man is not the only male figure who is mocked: even God cannot subjugate Lilith and needs to ask his messengers, who only manage to go as far as negotiating the conditions of the agreement.[47]

The Alphabet of Ben-Sira is the earliest surviving source of the story, and the conception that Lilith was Adam's first wife became only widely known with the 17th century Lexicon Talmudicum of German scholar Johannes Buxtorf.

In this folk tradition that arose in the early Middle Ages Lilith, a dominant female demon, became identified with Asmodeus, King of Demons, as his queen.[60] Asmodeus was already well known by this time because of the legends about him in the Talmud. Thus, the merging of Lilith and Asmodeus was inevitable.[61] The second myth of Lilith grew to include legends about another world and by some accounts this other world existed side by side with this one, Yenne Velt is Yiddish for this described "Other World". In this case Asmodeus and Lilith were believed to procreate demonic offspring endlessly and spread chaos at every turn.[62]

Two primary characteristics are seen in these legends about Lilith: Lilith as the incarnation of lust, causing men to be led astray, and Lilith as a child-killing witch, who strangles helpless neonates. These two aspects of the Lilith legend seemed to have evolved separately; there is hardly a tale where she encompasses both roles.[62] But the aspect of the witch-like role that Lilith plays broadens her archetype of the destructive side of witchcraft. Such stories are commonly found among Jewish folklore.[62]

The influence of the rabbinic traditions[edit]

Although the image of Lilith of the Alphabet of Ben Sira is unprecedented, some elements in her portrayal can be traced back to the talmudic and midrashic traditions that arose around Eve:

- First and foremost, the very introduction of Lilith to the creation story rests on the rabbinic myth, prompted by the two separate creation accounts in Genesis 1:1–2:25, that there were two original women. A way of resolving the apparent discrepancy between these two accounts was to assume that there must have been some other first woman, apart from the one later identified with Eve. The Rabbis, noting Adam's exclamation, "this time (zot hapa‘am) [this is] bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh" (Genesis 2:23), took it as an intimation that there must already have been a "first time". According to Genesis rabah 18:4, Adam was disgusted upon seeing the first woman full of "discharge and blood", and God had to provide him with another one. The subsequent creation is performed with adequate precautions: Adam is made to sleep, so as not to witness the process itself ( Sanhedrin 39a), and Eve is adorned with fine jewellery (Genesis rabah 18:1) and brought to Adam by the angels Gabriel and Michael (ibid. 18:3). However, nowhere do the rabbis specify what happened to the first woman, leaving the matter open for further speculation. This is the gap into which the later tradition of Lilith could fit.

- Second, this new woman is still met with harsh rabbinic allegations. Again playing on the Hebrew phrase zot hapa‘am, Adam, according to the same midrash, declares: "it is she [zot] who is destined to strike the bell [zog] and to speak [in strife] against me, as you read, 'a golden bell [pa‘amon] and a pomegranate' [Exodus 28:34] ... it is she who will trouble me [mefa‘amtani] all night" (Genesis Rabbah 18:4). The first woman also becomes the object of accusations ascribed to Rabbi Joshua of Siknin, according to whom Eve, despite the divine efforts, turned out to be "swelled-headed, coquette, eavesdropper, gossip, prone to jealousy, light-fingered and gadabout" (Genesis Rabbah 18:2). A similar set of charges appears in Genesis Rabbah 17:8, according to which Eve's creation from Adam's rib rather than from the earth makes her inferior to Adam and never satisfied with anything.

- Third, and despite the terseness of the biblical text in this regard, the erotic iniquities attributed to Eve constitute a separate category of her shortcomings. Told in Genesis 3:16 that "your desire shall be for your husband", she is accused by the Rabbis of having an overdeveloped sexual drive (Genesis Rabhah 20:7) and constantly enticing Adam (Genesis Rabbab 23:5). However, in terms of textual popularity and dissemination, the motif of Eve copulating with the primeval serpent takes priority over her other sexual transgressions. Despite the rather unsettling picturesqueness of this account, it is conveyed in numerous places: Genesis Rabbah 18:6, and BT Sotah 9b, Shabbat 145b–146a and 156a, Yevamot 103b and Avodah Zarah 22b.[47]

Kabbalah[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Kabbalah |

|---|

|

Kabbalistic mysticism attempted to establish a more exact relationship between Lilith and God. With her major characteristics having been well developed by the end of the Talmudic period, after six centuries had elapsed between the Aramaic incantation texts that mention Lilith and the early Spanish Kabbalistic writings in the 13th century, she reappears, and her life history becomes known in greater mythological detail.[63] Her creation is described in many alternative versions.

One mentions her creation as being before Adam's, on the fifth day, because the "living creatures" with whose swarms God filled the waters included Lilith. A similar version, related to the earlier Talmudic passages, recounts how Lilith was fashioned with the same substance as Adam was, shortly before. A third alternative version states that God originally created Adam and Lilith in a manner that the female creature was contained in the male. Lilith's soul was lodged in the depths of the Great Abyss. When God called her, she joined Adam. After Adam's body was created, a thousand souls from the Left (evil) side attempted to attach themselves to him. However, God drove them off. Adam was left lying as a body without a soul. Then a cloud descended and God commanded the earth to produce a living soul. This God breathed into Adam, who began to spring to life and his female was attached to his side. God separated the female from Adam's side. The female side was Lilith, whereupon she flew to the Cities of the Sea and attacked humankind.

Yet another version claims that Lilith emerged as a divine entity that was born spontaneously, either out of the Great Supernal Abyss or out of the power of an aspect of God (the Gevurah of Din). This aspect of God was negative and punitive, as well as one of his ten attributes (Sefirot), at its lowest manifestation has an affinity with the realm of evil and it is out of this that Lilith merged with Samael.[64]

An alternative story links Lilith with the creation of luminaries. The "first light", which is the light of Mercy (one of the Sefirot), appeared on the first day of creation when God said "Let there be light". This light became hidden and the Holiness became surrounded by a husk of evil. "A husk (klippa) was created around the brain" and this husk spread and brought out another husk, which was Lilith.[65]

Midrash ABKIR[edit]

The first medieval source to depict Adam and Lilith in full was the Midrash A.B.K.I.R. (c. 10th century), which was followed by the Zohar and other Kabbalistic writings. Adam is said to be perfect until he recognises either his sin or Cain's fratricide that is the cause of bringing death into the world. He then separates from holy Eve, sleeps alone, and fasts for 130 years. During this time "Pizna", either an alternate name for Lilith or a daughter of hers, desires his beauty and seduces him against his will. She gives birth to multitudes of djinns and demons, the first of them being named Agrimas. However, they are defeated by Methuselah, who slays thousands of them with a holy sword and forces Agrimas to give him the names of the rest, after which he casts them away to the sea and the mountains.[66]

Treatise on the Left Emanation[edit]

The mystical writing of two brothers Jacob and Isaac Hacohen, Treatise on the Left Emanation, which predates the Zohar by a few decades, states that Samael and Lilith are in the shape of an androgynous being, double-faced, born out of the emanation of the Throne of Glory and corresponding in the spiritual realm to Adam and Eve, who were likewise born as a hermaphrodite. The two twin androgynous couples resembled each other and both "were like the image of Above"; that is, that they are reproduced in a visible form of an androgynous deity.

Another version[68] that was also current among Kabbalistic circles in the Middle Ages establishes Lilith as the first of Samael's four wives: Lilith, Naamah, Eisheth, and Agrat bat Mahlat. Each of them are mothers of demons and have their own hosts and unclean spirits in no number.[69] The marriage of archangel Samael and Lilith was arranged by "Blind Dragon", who is the counterpart of "the dragon that is in the sea". Blind Dragon acts as an intermediary between Lilith and Samael:

The marriage of Samael and Lilith is known as the "Angel Satan" or the "Other God", but it was not allowed to last. To prevent Lilith and Samael's demonic children Lilin from filling the world, God castrated Samael. In many 17th century Kabbalistic books, this seems to be a reinterpretation of an old Talmudic myth where God castrated the male Leviathan and slew the female Leviathan in order to prevent them from mating and thereby destroying the Earth with their offspring.[71] With Lilith being unable to fornicate with Samael anymore, she sought to couple with men who experience nocturnal emissions. A 15th or 16th century Kabbalah text states that God has "cooled" the female Leviathan, meaning that he has made Lilith infertile and she is a mere fornication.

The Treatise on the Left Emanation also says that there are two Liliths, the lesser being married to the great demon Asmodeus.

Another passage charges Lilith as being a tempting serpent of Eve.

Zohar[edit]

References to Lilith in the Zohar include the following:

This passage may be related to the mention of Lilith in Talmud Shabbath 151b (see above), and also to Talmud Eruvin 18b where nocturnal emissions are connected with the begettal of demons.

According to Rapahel Patai, older sources state clearly that after Lilith's Red Sea sojourn (mentioned also in Louis Ginzberg's Legends of the Jews), she returned to Adam and begat children from him by forcing herself upon him. Before doing so, she attaches herself to Cain and bears him numerous spirits and demons. In the Zohar, however, Lilith is said to have succeeded in begetting offspring from Adam even during their short-lived sexual experience. Lilith leaves Adam in Eden, as she is not a suitable helpmate for him.[74] Gershom Scholem proposes that the author of the Zohar, Rabbi Moses de Leon, was aware of both the folk tradition of Lilith and another conflicting version, possibly older.[75]

The Zohar adds further that two female spirits instead of one, Lilith and Naamah, desired Adam and seduced him. The issue of these unions were demons and spirits called "the plagues of humankind", and the usual added explanation was that it was through Adam's own sin that Lilith overcame him against his will.[74]

17th-century Hebrew magical amulets[edit]

A copy of Jean de Pauly's translation of the Zohar in the Ritman Library contains an inserted late 17th century printed Hebrew sheet for use in magical amulets where the prophet Elijah confronts Lilith.[76]

The sheet contains two texts within borders, which are amulets, one for a male ('lazakhar'), the other one for a female ('lanekevah'). The invocations mention Adam, Eve and Lilith, 'Chavah Rishonah' (the first Eve, who is identical with Lilith), also devils or angels: Sanoy, Sansinoy, Smangeluf, Shmari'el (the guardian) and Hasdi'el (the merciful). A few lines in Yiddish are followed by the dialogue between the prophet Elijah and Lilith when he met her with her host of demons to kill the mother and take her new-born child ('to drink her blood, suck her bones and eat her flesh'). She tells Elijah that she will lose her power if someone uses her secret names, which she reveals at the end: lilith, abitu, abizu, hakash, avers hikpodu, ayalu, matrota ...[77]

In other amulets, probably informed by The Alphabet of Ben-Sira, she is Adam's first wife. (Yalqut Reubeni, Zohar 1:34b, 3:19[78])

Charles Richardson's dictionary portion of the Encyclopædia Metropolitana appends to his etymological discussion of lullaby "a [manuscript] note written in a copy of Skinner" [i.e. Stephen Skinner's 1671 Etymologicon Linguæ Anglicanæ], which asserts that the word lullaby originates from Lillu abi abi, a Hebrew incantation meaning "Lilith begone" recited by Jewish mothers over an infant's cradle.[79] Richardson did not endorse the theory and modern lexicographers consider it a false etymology.[79][80]

Greco-Roman mythology[edit]

In the Latin Vulgate Book of Isaiah 34:14, Lilith is translated lamia.

According to Augustine Calmet, Lilith has connections with early views on vampires and sorcery:

According to Siegmund Hurwitz the Talmudic Lilith is connected with the Greek Lamia, who, according to Hurwitz, likewise governed a class of child stealing lamia-demons. Lamia bore the title "child killer" and was feared for her malevolence, like Lilith. She has different conflicting origins and is described as having a human upper body from the waist up and a serpentine body from the waist down.[82] One source states simply that she is a daughter of the goddess Hecate, another, that Lamia was subsequently cursed by the goddess Hera to have stillborn children because of her association with Zeus; alternatively, Hera slew all of Lamia's children (except Scylla) in anger that Lamia slept with her husband, Zeus. The grief caused Lamia to turn into a monster that took revenge on mothers by stealing their children and devouring them.[82] Lamia had a vicious sexual appetite that matched her cannibalistic appetite for children. She was notorious for being a vampiric spirit and loved sucking men's blood.[83] Her gift was the "mark of a Sibyl", a gift of second sight. Zeus was said to have given her the gift of sight. However, she was "cursed" to never be able to shut her eyes so that she would forever obsess over her dead children. Taking pity on Lamia, Zeus gave her the ability to remove and replace her eyes from their sockets.[82]

Arabic literature[edit]

Lilith is not found in the Quran or Hadith. The Sufi occult writer Ahmad al-Buni (d. 1225), in his Sun of the Great Knowledge (Arabic: شمس المعارف الكبرى), mentions a demon called "the mother of children" (ام الصبيان), a term also used "in one place".[84]

In Western literature[edit]

In German literature[edit]

Lilith's earliest appearance in the literature of the Romantic period (1789–1832) was in Goethe's 1808 work Faust: The First Part of the Tragedy.

After Mephistopheles offers this warning to Faust, he then, quite ironically, encourages Faust to dance with "the Pretty Witch". Lilith and Faust engage in a short dialogue, where Lilith recounts the days spent in Eden.

In English literature[edit]

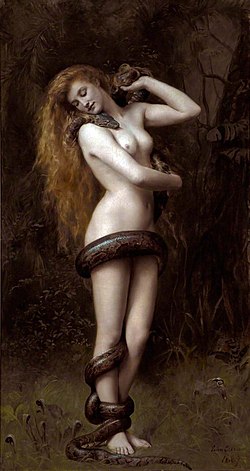

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which developed around 1848,[85] were greatly influenced by Goethe's work on the theme of Lilith. In 1863, Dante Gabriel Rossetti of the Brotherhood began painting what would later be his first rendition of Lady Lilith, a painting he expected to be his "best picture hitherto".[85] Symbols appearing in the painting allude to the "femme fatale" reputation of the Romantic Lilith: poppies (death and cold) and white roses (sterile passion). Accompanying his Lady Lilith painting from 1866, Rossetti wrote a sonnet entitled Lilith, which was first published in Swinburne's pamphlet-review (1868), Notes on the Royal Academy Exhibition.

The poem and the picture appeared together alongside Rossetti's painting Sibylla Palmifera and the sonnet Soul's Beauty. In 1881, the Lilith sonnet was renamed "Body's Beauty" in order to contrast it and Soul's Beauty. The two were placed sequentially in The House of Life collection (sonnets number 77 and 78).[85]

Rossetti wrote in 1870:

This is in accordance with Jewish folk tradition, which associates Lilith both with long hair (a symbol of dangerous feminine seductive power in Jewish culture), and with possessing women by entering them through mirrors.[86]

The Victorian poet Robert Browning re-envisioned Lilith in his poem "Adam, Lilith, and Eve". First published in 1883, the poem uses the traditional myths surrounding the triad of Adam, Eve, and Lilith. Browning depicts Lilith and Eve as being friendly and complicitous with each other, as they sit together on either side of Adam. Under the threat of death, Eve admits that she never loved Adam, while Lilith confesses that she always loved him:

Browning focused on Lilith's emotional attributes, rather than that of her ancient demon predecessors.[87]

Scottish author George MacDonald also wrote a fantasy novel entitled Lilith, first published in 1895. MacDonald employed the character of Lilith in service to a spiritual drama about sin and redemption, in which Lilith finds a hard-won salvation. Many of the traditional characteristics of Lilith mythology are present in the author's depiction: Long dark hair, pale skin, a hatred and fear of children and babies, and an obsession with gazing at herself in a mirror. MacDonald's Lilith also has vampiric qualities: she bites people and sucks their blood for sustenance.

Australian poet and scholar Christopher John Brennan (1870–1932), included a section titled "Lilith" in his major work "Poems: 1913" (Sydney : G. B. Philip and Son, 1914). The "Lilith" section contains thirteen poems exploring the Lilith myth and is central to the meaning of the collection as a whole.

C. L. Moore's 1940 story Fruit of Knowledge is written from Lilith's point of view. It is a re-telling of the Fall of Man as a love triangle between Lilith, Adam and Eve – with Eve's eating the forbidden fruit being in this version the result of misguided manipulations by the jealous Lilith, who had hoped to get her rival discredited and destroyed by God and thus regain Adam's love.

British poet John Siddique's 2011 collection Full Blood has a suite of 11 poems called The Tree of Life, which features Lilith as the divine feminine aspect of God. A number of the poems feature Lilith directly, including the piece Unwritten which deals with the spiritual problem of the feminine being removed by the scribes from The Bible.

Lilith is also mentioned in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, by C.S.Lewis. The character Mr. Beaver ascribes the ancestry of the main antagonist, Jadis the White Witch, to Lilith.[88]

In modern occultism and Western esotericism[edit]

The depiction of Lilith in Romanticism continues to be popular among Wiccans and in other modern Occultism.[85] A few magical orders dedicated to the undercurrent of Lilith, featuring initiations specifically related to the arcana of the "first mother", exist. Two organisations that use initiations and magic associated with Lilith are the Ordo Antichristianus Illuminati and the Order of Phosphorus. Lilith appears as a succubus in Aleister Crowley's De Arte Magica. Lilith was also one of the middle names of Crowley's first child, Nuit Ma Ahathoor Hecate Sappho Jezebel Lilith Crowley (1904–1906), and Lilith is sometimes identified with Babalon in Thelemic writings. Many early occult writers that contributed to modern day Wicca expressed special reverence for Lilith. Charles Leland associated Aradia with Lilith: Aradia, says Leland, is Herodias, who was regarded in stregheria folklore as being associated with Diana as chief of the witches. Leland further notes that Herodias is a name that comes from west Asia, where it denoted an early form of Lilith.[89][90]

Gerald Gardner asserted that there was continuous historical worship of Lilith to present day, and that her name is sometimes given to the goddess being personified in the coven by the priestess. This idea was further attested by Doreen Valiente, who cited her as a presiding goddess of the Craft: "the personification of erotic dreams, the suppressed desire for delights".[91] In some contemporary concepts, Lilith is viewed as the embodiment of the Goddess, a designation that is thought to be shared with what these faiths believe to be her counterparts: Inanna, Ishtar, Asherah, Anath and Isis.[92] According to one view, Lilith was originally a Sumerian, Babylonian, or Hebrew mother goddess of childbirth, children, women, and sexuality.[93][94]

Raymond Buckland holds that Lilith is a dark moon goddess on par with the Hindu Kali.[95][page needed]

Many modern theistic Satanists consider Lilith as a goddess. She is considered a goddess of independence by those Satanists and is often worshipped by women, but women are not the only people who worship her. Lilith is popular among theistic Satanists because of her association with Satan. Some Satanists believe that she is the wife of Satan and thus think of her as a mother figure. Others base their reverence towards her based on her history as a succubus and praise her as a sex goddess.[96] A different approach to a Satanic Lilith holds that she was once a fertility and agricultural goddess.[97]

The western mystery tradition associates Lilith with the Qliphoth of kabbalah. Samael Aun Weor in The Pistis Sophia Unveiled writes that homosexuals are the "henchmen of Lilith". Likewise, women who undergo wilful abortion, and those who support this practice are "seen in the sphere of Lilith".[98] Dion Fortune writes, "The Virgin Mary is reflected in Lilith",[99] and that Lilith is the source of "lustful dreams".[99]

Popular culture[edit]

See also[edit]

- Eve

- Mesopotamian Religion

- Lilu, Akkadian demons

- Lilin, Hebrew term of demons in Targum Sheni Esther 1:3 and Apocalypse of Baruch

- Lilith (Lurianic Kabbalah)

- Lilith Fair

- Abyzou

- Daemon (classical mythology)

- Ishtar

- Inanna

- Norea

- Serpent seed

- Siren

- Spirit spouse

- Succubus

Notes[edit]

- ^ Hammer, Jill. "Lilith, Lady Flying in Darkness". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved 19 June2017.

- ^ Schwartz, Howard (2006). Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. Oxford University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-19-532713-7.

- ^ a b Kvam, Kristen E.; Schearing, Linda S.; Ziegler, Valarie H. (1999). Eve and Adam: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Readings on Genesis and Gender. Indiana University Press. pp. 220–1. ISBN 978-0-253-21271-9.

- ^ Freedman, David Noel (ed.) (1997, 1992). Anchor Bible Dictionary. New York: Doubleday. "Very little information has been found relating to the Akkadian and Babylonian view of these figures. Two sources of information previously used to define Lilith are both suspect."

- ^ Erich Ebeling, Bruno Meissner, Dietz Otto Edzard Reallexikon der Assyriologie Volume 9 p 47, 50.[verification needed]

- ^ Michael C. Astour Hellenosemitica: an ethnic and cultural study in west Semitic impact on Mycenaean. Greece 1965 Brill p 138.

- ^ Sayce (1887)[page needed]

- ^ Fossey (1902)[page needed]

- ^ Kramer, S. N. Gilgamesh and the Huluppu-Tree: A Reconstructed Sumerian Text. Assyriological Studies 10. Chicago. 1938.

- ^ George, A. The epic of Gilgamesh: the Babylonian epic poem and other texts in Akkadian2003 p 100 Tablet XII. Appendix The last Tablet in the 'Series of Gilgamesh' .

- ^ Kramer translates the zu as "owl", but most often it is translated as "eagle", "vulture", or "bird of prey".

- ^ Chicago Assyrian Dictionary. Chicago: University of Chicago. 1956.

- ^ Hurwitz (1980) p. 49

- ^ Manfred Hutter article in Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter Willem van der Horst – 1999 pp. 520–521, article cites Hutter's own 1988 work Behexung, Entsühnung und HeilungEisenbrauns 1988. pp. 224–228.

- ^ Müller-Kessler, C. (2002) "A Charm against Demons of Time", in C. Wunsch (ed.), Mining the Archives. Festschrift Christopher Walker on the Occasion of his 60th Birthday (Dresden), p. 185.

- ^ Roberta Sterman Sabbath Sacred tropes: Tanakh, New Testament, and Qur'an as literature and culture 2009.

- ^ Sex and gender in the ancient Near East: proceedings of the 47th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Helsinki, July 2–6, 2001, Part 2 p. 481.

- ^ Opitz, D. Ausgrabungen und Forschungsreisen Ur. AfO 8: 328.

- ^ Ribichini, S. Lilith nell-albero Huluppu Pp. 25 in Atti del 1° Convegno Italiano sul Vicino Oriente Antico, Rome, 1976.

- ^ Frankfort, H. The Burney Relief AfO 12: 128, 1937.

- ^ Kraeling, E. G. A Unique Babylonian Relief BASOR 67: 168. 1937.

- ^ Kraeling, Emil (1937). "A Unique Babylonian Relief". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 67 (67): 16–18. doi:10.2307/3218905. JSTOR 3218905. S2CID 164141131.

- ^ Albenda, Pauline (2005). "The "Queen of the Night" Plaque: A Revisit". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 125 (2): 171–190. JSTOR 20064325.

- ^ Gaster, T. H. 1942. A Canaanite Magical Text. Or 11:

- ^ Torczyner, H. 1947. "A Hebrew Incantation against Night-Demons from Biblical Times". JNES 6: 18–29.

- ^ Isaiah 34:14

- ^ de Waard, Jan (1997). A handbook on Isaiah. Winona Lake, IN. ISBN 1-57506-023-X.

- ^ Delitzsch Isaiah.

- ^ See The animals mentioned in the Bible Henry Chichester Hart 1888, and more modern sources; also entries Brown Driver Briggs Hebrew Lexicon for tsiyyim... 'iyyim... sayir... liylith... qippowz... dayah.

- ^ "Isaiah 34:14 (JPS 1917)". Mechon Mamre. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ (מנוח manoaḥ, used for birds as Noah's dove, Gen.8:9 and also humans as Israel, Deut.28:65; Naomi, Ruth 3:1).

- ^ Blair J. "De-demonising the Old Testament" p.27.

- ^ Christopher R. A. Morray-Jones A transparent illusion: the dangerous vision of water in Hekhalot Vol. 59 p 258 2002 "Early evidence of the belief in a plurality of liliths is provided by the Isaiah scroll from Qumran, which gives the name as liliyyot, and by the targum to Isaiah, which, in both cases, reads" (Targum reads: "when Lilith the Queen of [Sheba] and of Margod fell upon them.")

- ^ Jahrbuch für Protestantische Theologie 1, 1875. p 128.

- ^ Levy, [Moritz] A.[braham] (1817–1872)]. Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenländischen Gesellschaft. ZDMG 9. 1885. pp. 470, 484.

- ^ Judit M. Blair (2009). De-Demonising the Old Testament – An Investigation of Azazel, Lilit (Lilith), Deber (Dever), Qeteb (Qetev) and Reshep (Resheph) in the Hebrew Bible. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 2 Reihe. Tübingen. ISBN 978-3-16-150131-9.

- ^ 34:14 καὶ συναντήσουσιν δαιμόνια ὀνοκενταύροις καὶ βοήσουσιν ἕτερος πρὸς τὸν ἕτερον ἐκεῖ ἀναπαύσονται ὀνοκένταυροι εὗρον γὰρ αὑτοῖς ἀνάπαυσιν

Translation: And daemons shall meet with onocentaurs, and they shall cry one to the other: there shall the onocentaurs rest, having found for themselves [a place of] rest. - ^ "The Old Testament (Vulgate)/Isaias propheta". Wikisource (Latin). Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- ^ "Parallel Latin Vulgate Bible and Douay-Rheims Bible and King James Bible; The Complete Sayings of Jesus Christ". Latin Vulgate. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Michael T. Davis, Brent A. Strawn Qumran studies: new approaches, new questions 2007 p 47: "two manuscripts that date to the Herodian period, with 4Q510 slightly earlier".

- ^ Bruce Chilton, Darrell Bock, Daniel M. Gurtner A Comparative Handbook to the Gospel of Mark p 84.

- ^ "Lilith". Biblical Archaeology Society. 2019-10-31. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ^ Revue de Qumrân 1991 p 133.

- ^ Baumgarten, J. M. "On the Nature of the Seductress in 4Q184", Revue de Qumran 15 (1991–2), 133–143; "The seductress of Qumran", Bible Review 17 no 5 (2001), 21–23; 42.

- ^ Collins, Jewish wisdom in the Hellenistic age.

- ^ Tractate Niddah in the Mishnah is the only tractate from the Order of Tohorot which has Talmud on it. The Jerusalem Talmud is incomplete here, but the Babylonian Talmud on Tractate Niddah (2a–76b) is complete.

- ^ a b c d e f Kosior, Wojciech (2018). "A Tale of Two Sisters: The Image of Eve in Early Rabbinic Literature and Its Influence on the Portrayal of Lilith in the Alphabet of Ben Sira". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (32): 112–130. doi:10.2979/nashim.32.1.10. S2CID 166142604.

- ^ Aish. "Lillith". Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Numbers Rabbah, in: Judaic Classics Library, Davka Corporation, 1999. (CD-ROM).

- ^ a b c Shaked, Shaul (2013). Aramaic bowl spells : Jewish Babylonian Aramaic bowls. Volume one. Ford, James Nathan; Bhayro, Siam; Morgenstern, Matthew; Vilozny, Naama. Leiden. ISBN 9789004229372. OCLC 854568886.

- ^ a b Lesses, Rebecca (2001). "Exe(o)rcising Power: Women as Sorceresses, Exorcists, and Demonesses in Babylonian Jewish Society of Late Antiquity". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 69 (2): 343–375. doi:10.1093/jaarel/69.2.343. ISSN 0002-7189. JSTOR 1465786. PMID 20681106.

- ^ Descenders to the chariot: the people behind the Hekhalot literature, p. 277 James R. Davila – 2001: "that they be used by anyone and everyone. The whole community could become the equals of the sages. Perhaps this is why nearly every house excavated in the Jewish settlement in Nippur had one or more incantation bowl buried in it."

- ^ Yamauchi, Edwin M. (October–December 1965). "Aramaic Magic Bowls". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 85 (4): 511–523. doi:10.2307/596720. JSTOR 596720.

- ^ Isbell, Charles D. (March 1978). "The Story of the Aramaic Magical Incantation Bowls". The Biblical Archaeologist. 41 (1): 5–16. doi:10.2307/3209471. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3209471.

- ^ Full text in p 156 Aramaic Incantation Texts from Nippur James Alan Montgomery – 2011.

- ^ The attribution to the sage Ben Sira is considered false, with the true author unknown.

- ^ Alphabet of Ben Sirah, Question #5 (23a–b).

- ^ Humm, Alan. Lilith in the Alphabet of Ben Sira

- ^ Segal, Eliezer. Looking for Lilith

- ^ Schwartz p. 7.

- ^ Schwartz p 8.

- ^ a b c Schwartz p. 8.

- ^ Patai pp. 229–230.

- ^ Patai p. 230.

- ^ Patai p. 231.

- ^ Geoffrey W. Dennis, The Encyclopedia of Jewish Myth, Magic and Mysticism: Second Edition.

- ^ Patai p.231.

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia demonology

- ^ Patai p. 244.

- ^ Humm, Alan. Lilith, Samael, & Blind Dragon

- ^ Patai p. 246.

- ^ R. Isaac b. Jacob Ha-Kohen. Lilith in Jewish Mysticism: Treatise on the Left Emanation

- ^ Patai p. 233.

- ^ a b Patai p 232 "But Lilith, whose name is Pizna, - or according to the Zohar, two female spirits, Lilith and Naamah — found him, desired his beauty which was like that of the sun disk, and lay with him. The issue of these unions were demons and spirits"

- ^ Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, p. 174.

- ^ "Printed sheet, late 17th century or early 18th century, 185x130 mm.

- ^ "Lilith Amulet-J.R. Ritman Library". Archived from the original on 2010-02-12.

- ^ Humm, Alan. Kabbalah: Lilith's origins

- ^ a b Richardson, Charles (1845). "Lexicon: Lull, Lullaby". In Smedley, Edward; Rose, Hugh James; Rose, Edward John (eds.). Encyclopædia Metropolitana. XXI. London. pp. 597–598. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "lullaby". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 18 June 2020.; "lullaby". American Heritage Dictionary (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 18 June 2020.; Simpson, John A., ed. (1989). "lullaby". The Oxford English dictionary. IX(2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 93. Retrieved 18 June 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Calmet, Augustine (1751). Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016. p. 353. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

- ^ a b c Hurwitz p. 43.

- ^ Hurwitz p. 78.

- ^ "an eine Stelle" Hurwitz S. Die erste Eva: Eine historische und psychologische Studie2004 Page 160 "8) Lilith in der arabischen Literatur: Die Karina Auch in der arabischen Literatur hat der Lilith-Mythos seinen Niederschlag gefunden."

- ^ a b c d e Amy Scerba. "Changing Literary Representations of Lilith and the Evolution of a Mythical Heroine". Archived from the original on 2011-12-21. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- ^ Howard Schwartz (1988). Lilith's Cave: Jewish tales of the supernatural. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

- ^ Seidel, Kathryn Lee. The Lilith Figure in Toni Morrison's Sula and Alice Walker's The Color Purple

- ^ The Lion, the Witch, and Wardrobe, Collier Books (paperback, Macmillan subsidiary), 1970, pg. 77.

- ^ Grimassi, Raven.Stregheria: La Vecchia Religione

- ^ Leland, Charles.Aradia, Gospel of the Witches-Appendix

- ^ "Lilith-The First Eve". Imbolc. 2002.

- ^ Grenn, Deborah J.History of Lilith Institute

- ^ Hurwitz, Siegmund. "Excerpts from Lilith-The first Eve".

- ^ "Lilith". Goddess. Archived from the original on 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ Raymond Buckland, The Witch Book, Visible Ink Press, November 1, 2001.

- ^ Margi Bailobiginki. "Lilith and the modern Western world". Theistic Satanism. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Charles Moffat. "The Sumerian legend of Lilith". Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Aun Weor, Samael (June 2005). Pistis Sophia Unveiled. p. 339. ISBN 9780974591681.

- ^ a b Fortune, Dion (1963). Psychic Self-Defence. pp. 126–128. ISBN 9781609254643.

References[edit]

- Talmudic References: b. Erubin 18b; b. Erubin 100b; b. Nidda 24b; b. Shab. 151b; b. Baba Bathra 73a–b

- Kabbalist References: Zohar 3:76b–77a; Zohar Sitrei Torah 1:147b–148b; Zohar 2:267b; Bacharach,'Emeq haMelekh, 19c; Zohar 3:19a; Bacharach,'Emeq haMelekh, 102d–103a; Zohar 1:54b–55a

- Dead Sea Scroll References: 4QSongs of the Sage/4QShir; 4Q510 frag.11.4–6a//frag.10.1f; 11QPsAp

- Lilith Bibliography, Jewish and Christian Literature, Alan Humm ed., 4 December 2020.

- Charles Fossey, La Magie Assyrienne, Paris: 1902.

- Siegmund Hurwitz, Lilith, die erste Eva: eine Studie über dunkle Aspekte des Weiblichen. Zürich: Daimon Verlag, 1980, 1993. English tr. Lilith, the First Eve: Historical and Psychological Aspects of the Dark Feminine, translated by Gela Jacobson. Einsiedeln, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag, 1992 ISBN 3-85630-545-9.

- Siegmund Hurwitz, Lilith Switzerland: Daminon Press, 1992. Jerusalem Bible. New York: Doubleday, 1966.

- Samuel Noah Kramer, Gilgamesh and the Huluppu-Tree: A reconstructed Sumerian Text. (Kramer's Translation of the Gilgamesh Prologue), Assyriological Studies of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 10, Chicago: 1938.

- Raphael Patai, Adam ve-Adama, tr. as Man and Earth; Jerusalem: The Hebrew Press Association, 1941–1942.

- Raphael Patai, The Hebrew Goddess, 3rd enlarged edition New York: Discus Books, 1978.

- Archibald Sayce, Hibbert Lectures on Babylonian Religion 1887.

- Schwartz, Howard, Lilith's Cave: Jewish tales of the supernatural, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988.

- R. Campbell Thompson, Semitic Magic, its Origin and Development, London: 1908.

- Isaiah, chapter 34. New American Bible

- Augustin Calmet, (1751) Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0

- Jeffers, Jen (2017) "Finding Lilith: The Most Powerful Hag In History". The Raven Report.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Lilith |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lilith. |

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Lilith

- Collection of Lilith information and links by Alan Humm

- International standard Bible Encyclopedia: Night-Monster

Comments

Post a Comment